The 2025 wildfire season has reinforced what Canadian emergency managers already know: structure protection is no longer an optional line item—it is critical infrastructure. With 8.78 million hectares burned as of September 16, 2025, ranking this season second only to the catastrophic 2023 fires, and devastating losses in communities from Jasper, Alberta to Denare Beach, Saskatchewan to Conception Bay North, Newfoundland and Labrador, the message is unmistakable: municipalities must act now to secure structure protection capacity for the 2026 fire season.

For procurement officers, fire chiefs, and municipal decision-makers across Canada, the fourth quarter of 2025—October through December—represents the most strategic window to begin specifying, scoping, and budgeting for wildfire structure protection equipment. Waiting until spring 2026 budget approval or summer procurement cycles will compress lead times, risk funding gaps, and potentially leave communities under-equipped when the next fire season arrives.

Canadian Wildfire Context: 2023–2025 Seasons and 2026 Outlook

Escalating Severity and Structure Loss

Canada's wildfire landscape has fundamentally shifted. The 2023 season burned 16.5 million hectares, shattering all previous records and producing more than double the area burned in any prior year. The 2024 season, while less extreme at 5.3 million hectares, still ranked as the sixth-worst on record and included the devastating Jasper wildfire, which destroyed 358 structures and generated $1.3 billion in insured losses—the second-most expensive natural disaster in Canadian history.

As of September 16, 2025, the current season has burned 8.78 million hectares across the country, trailing only 2023 since records began. Manitoba and Saskatchewan bore the brunt of the damage, with over half the total area burned occurring in these two provinces. More than 32,000 Manitobans registered with the Canadian Red Cross after evacuating their homes, and Flin Flon—a city of 5,000—faced a weeks-long evacuation beginning in late May.

Structure losses in 2025 have been catastrophic across multiple provinces. In Denare Beach, Saskatchewan, 218 homes were destroyed by the Wolf Fire, representing the vast majority of the province's 277 primary residential losses. An additional 60 cabins and 160 RVs were burned. The Flin Flon Wildfire Complex generated $249 million in insured damage across Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

Newfoundland and Labrador experienced unprecedented wildfire impacts in 2025. In early May, fires in Conception Bay North destroyed 12 homes and 45 other structures. The situation escalated dramatically in August when the Kingston wildfire ignited on August 3. By the time the fire was contained, 203 structures had been destroyed across nine communities, including homes in Kingston, Western Bay, Ochre Pit Cove, Northern Bay, and Adam's Cove, along with a school and post office. More than 3,000 residents were evacuated, and insured losses exceeded $70 million.

Climate-Driven Trends and the Wildland-Urban Interface

Canada is warming at twice the rate of the global average, with Northern Canada heating up at almost three times the global rate. Since 1948, Canada's annual average temperature over land has warmed 1.7°C, with higher rates seen in the North, the Prairies, and northern British Columbia. This warming has extended fire seasons, increased extreme fire weather, and intensified fire behavior.

Approximately 12.3% of the Canadian population lives in the wildland-urban interface (WUI), which includes 32.1% of on-reserve First Nations populations. Research examining Canadian buildings found that around 83.3% of structures (3,860,918 units) are exposed to wildfires, either directly within the WUI or in close proximity. Nationally, Canada has 32.3 million hectares of WUI, representing 3.8% of total national land area.

Looking Ahead to 2026

Forecasts for October through December 2025 predict above-normal temperatures across Alberta and much of western Canada, with precipitation forecasts showing below-average rainfall in key regions. Alberta's Wildfire Predictive Services reported in July 2025 that the province had experienced 108% more wildfires and burned 159% more hectares than the five-year average for that time of year, and forecasts called for fire activity to remain above normal through September. Natural Resources Canada modeling indicated elevated fire risk for the northern prairies, south-central British Columbia, and northwestern Ontario into late 2025.

Municipal and Agency Budget Cycles in Canada

Fiscal Year Structures and Budget Development Timelines

Most Canadian municipalities operate on a calendar-year fiscal cycle (January 1 to December 31), with the notable exception of Nova Scotia municipalities, which align with provincial and federal governments on an April 1 to March 31 fiscal year. Budget development for the upcoming fiscal year typically begins in the preceding fall, with capital and operating budgets finalized and approved in the fourth quarter or early weeks of the new calendar year.

Typical Municipal Budget Timeline (for January–December 2026 fiscal year):

July–October 2025: Finance departments receive proposals from operational divisions; initial capital project lists developed; preliminary budget guidelines established.

November–December 2025: Draft budgets compiled; management reviews conducted; service level discussions initiated; council presentations prepared.

Late December 2025: Budget presentations to council; public consultations; council deliberations and amendments; final budget adoption.

January 2026: Fiscal year begins; tax rate bylaws passed; procurement processes commence.

Nova Scotia Municipal Timeline (for April 2026 – March 2027 fiscal year):

Nova Scotia municipalities follow the provincial government's April–March fiscal year. Budget deliberations occur in the first quarter of the calendar year, with approval before April 1.

Critically, capital specifications and project scopes must be largely complete before the budget is presented to council. This means the work to define equipment needs, obtain preliminary quotes, validate compliance requirements, and develop business cases must occur in Q4 2025 (October–December) to align with budget submission deadlines.

Trade Agreement and Procurement Requirements

For structure protection equipment—which typically involves capital expenditures exceeding provincial trade agreement thresholds ($75,000 for goods/services; $200,000 for construction under the New West Partnership Trade Agreement in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia; higher thresholds under CFTA in other jurisdictions)—competitive public procurement is required.

British Columbia municipalities must typically allow a minimum bidding period of 15 days, with some trade agreements requiring 40+ days for certain thresholds. Municipalities that delay specification work until after budget approval face critical compression: they must rush development, limit supplier outreach, and risk missing grant application deadlines or procurement windows entirely.

Why Q4 2025 Is Critical for 2026 Procurement

Lead Time Realities for Structure Protection Equipment

Fire apparatus manufacturers report significant lead time challenges. Industry sources document that fire apparatus (pumper trucks, tankers) face lead times of 24–36+ months from order to delivery, with manufacturers reporting multi-year backlogs due to chassis shortages, labor constraints, and post-pandemic supply chain disruptions. Fire apparatus manufacturers report labor shortages, particularly for certified Emergency Vehicle Technicians (EVTs) and skilled trades. One Ontario fire chief noted that apparatus costs have increased from $600,000 to $900,000 in just a few years, with delivery timelines extending from months to years.

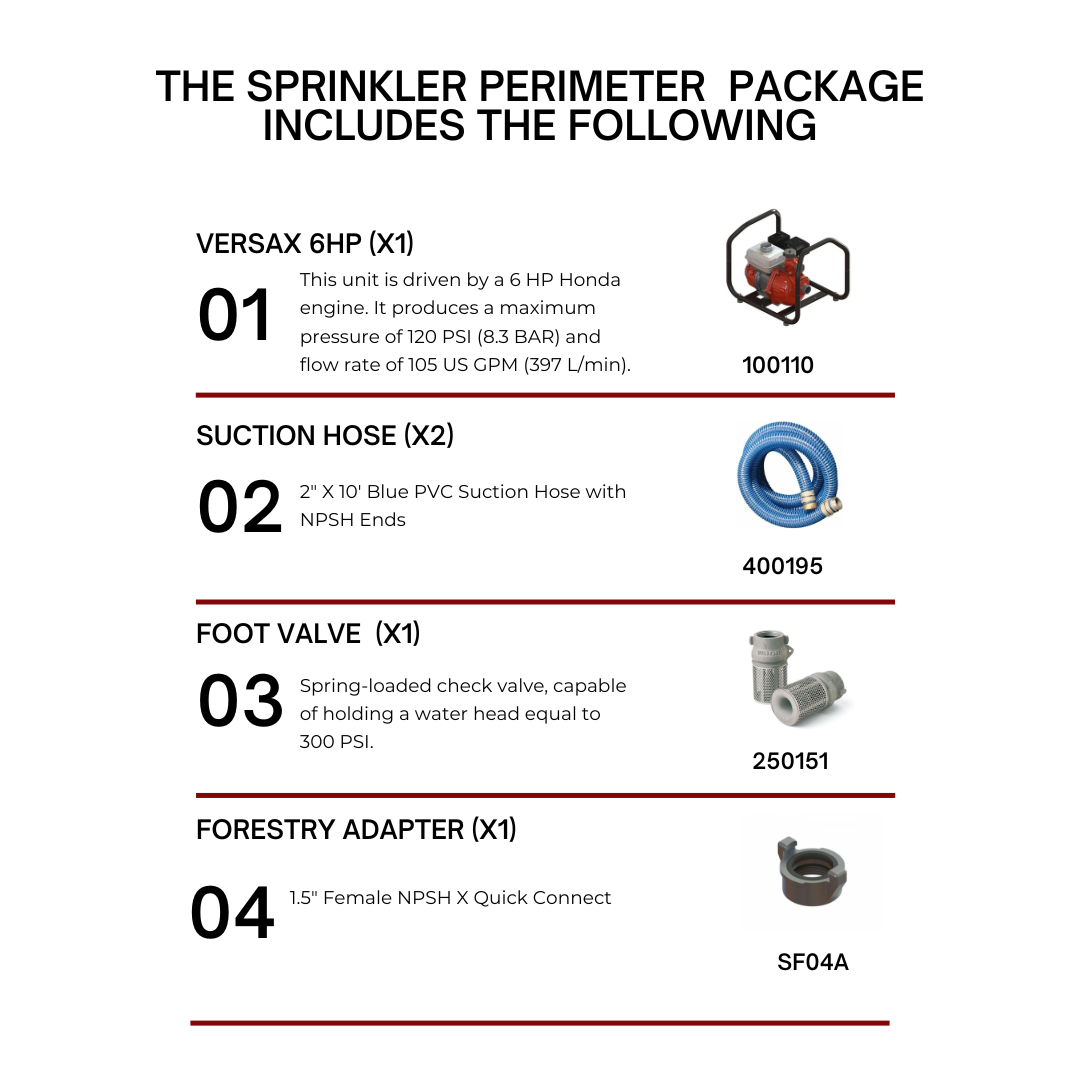

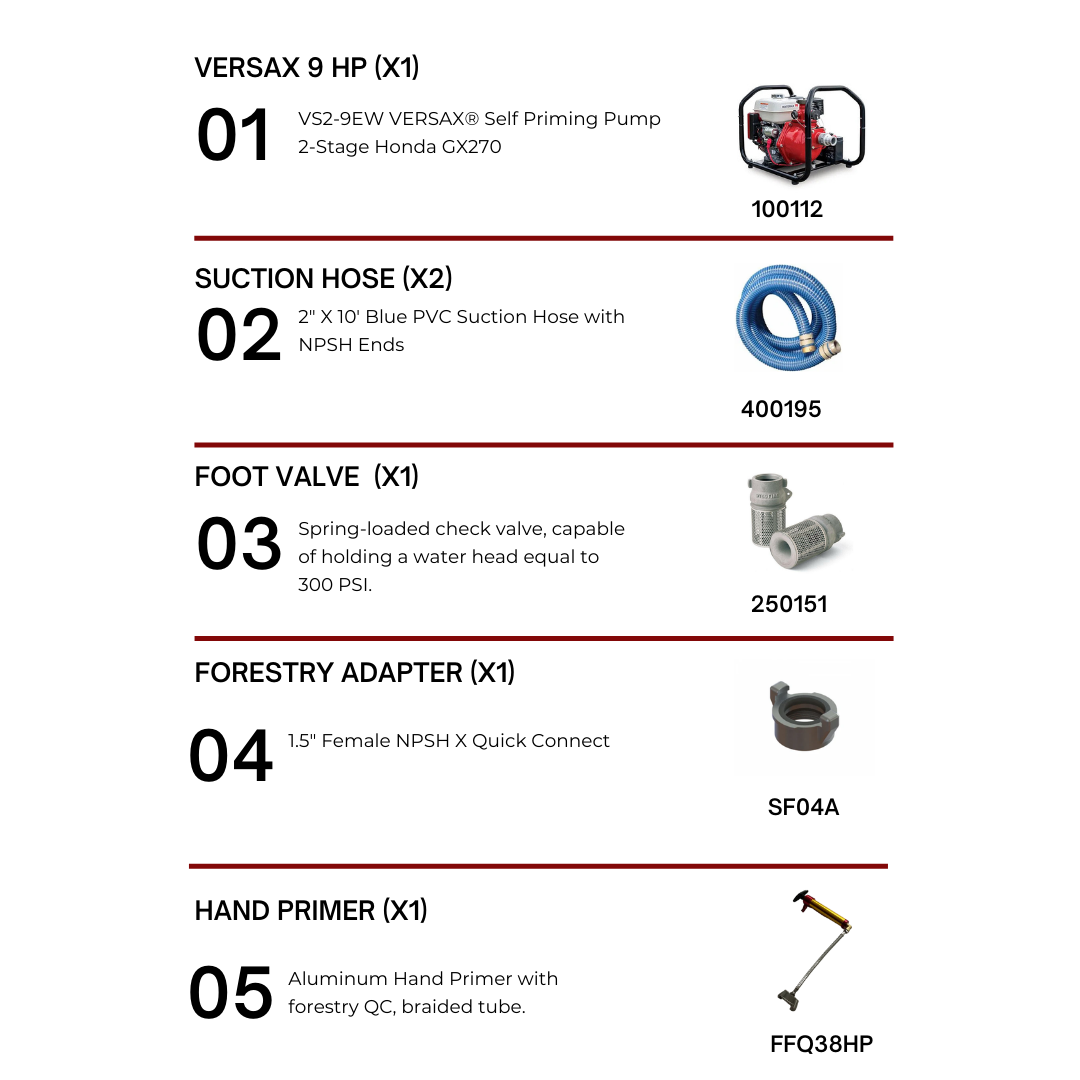

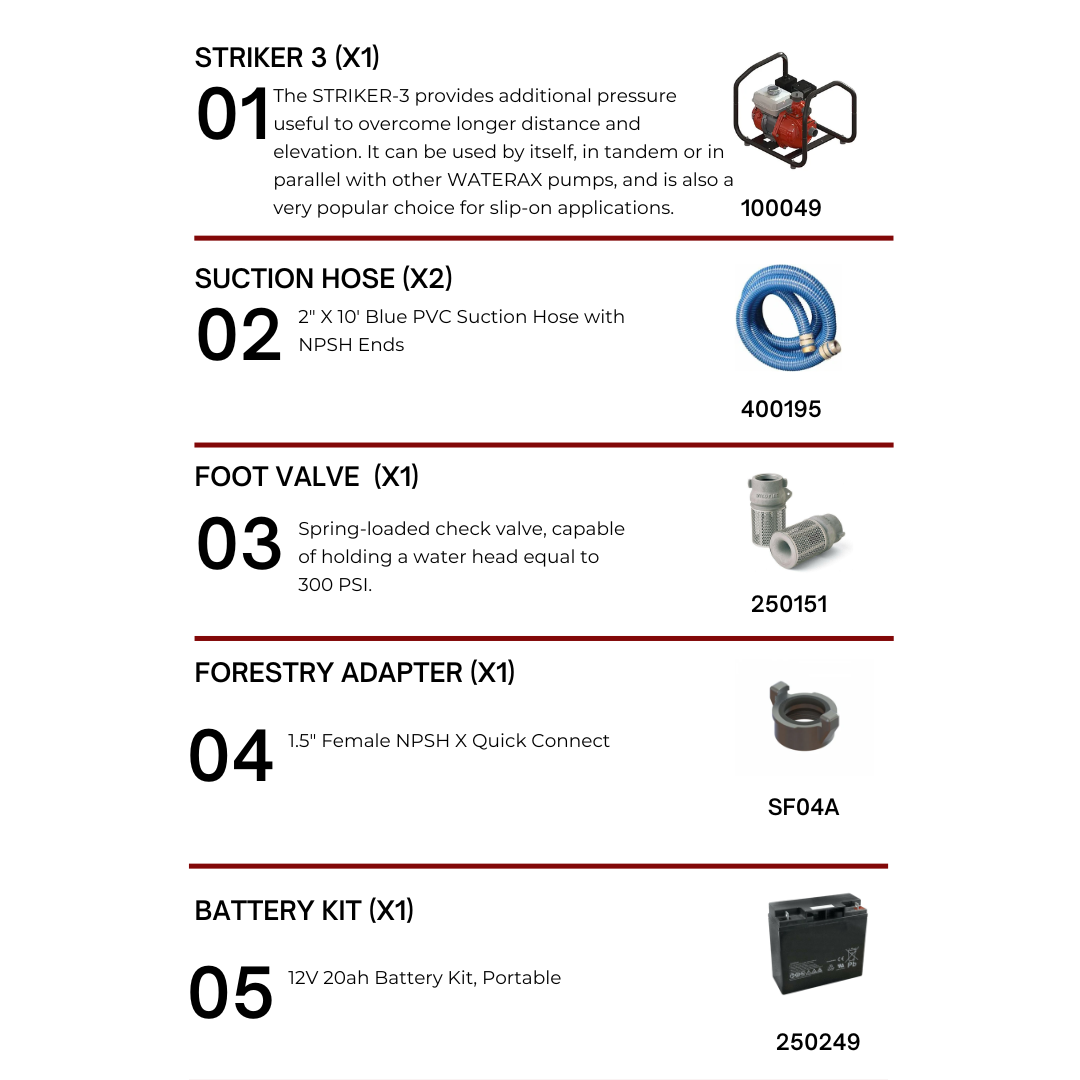

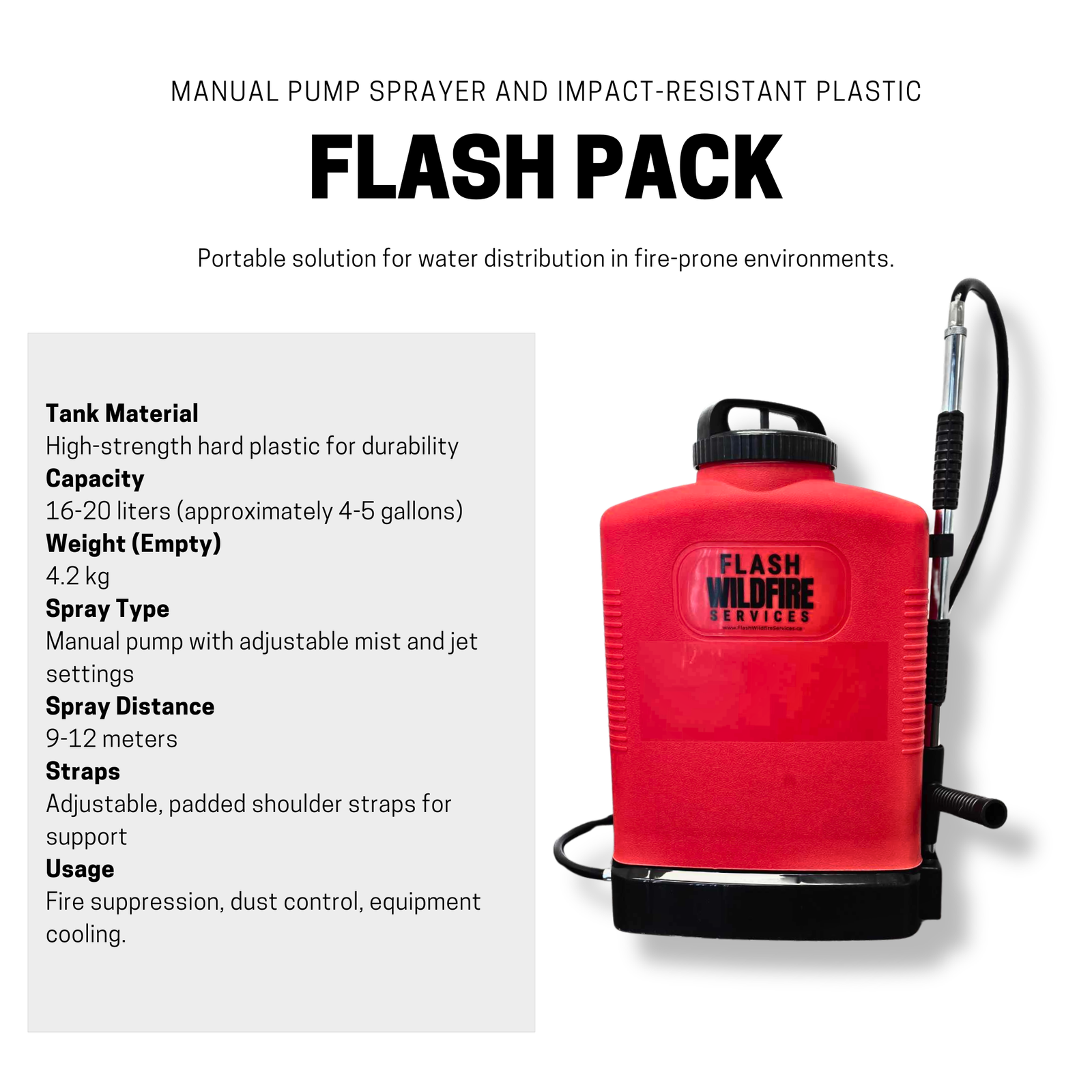

For other structure protection equipment—including sprinkler trailers, pumps, hoses, fittings, nozzles, and portable tanks—municipalities should contact suppliers early in the planning cycle to confirm current availability and lead times, as these vary significantly by vendor, season, and market conditions.

If a municipality begins procurement in May 2026 and completes the full procurement cycle, equipment may not arrive until well into 2027—missing the entire 2026 fire season. By contrast, municipalities that finalize specifications in Q4 2025 and secure budget approval in December 2025 or early 2026 can issue requests for proposals earlier in 2026.

Supply Chain Challenges

Chassis suppliers have multi-year backlogs, and component availability remains unpredictable. When fire conditions intensify in May and June, agencies across North America simultaneously seek equipment, creating bottlenecks and inflating prices. Municipalities that have pre-positioned orders through early procurement can avoid these seasonal demand surges.

Grant and Funding Alignment

Federal and provincial wildfire mitigation funding programs operate on specific application windows and fiscal year cycles. Missing these deadlines can defer projects by an entire year and forfeit substantial cost-sharing opportunities.

Key Funding Programs for 2025–2026:

FireSmart Community Funding and Supports (BC): Open intake from October 1, 2025 to September 30, 2026. Eligible applicants in high-risk WUI zones (Risk Class 1–3) can apply for up to $200,000 per year for up to two years for FireSmart activities, including structure protection planning and equipment. Applications require approved Community Wildfire Resiliency Plans (CWRPs).

Resilient Communities through FireSmart (RCF) Program (Federal): Announced in June 2025, this $104 million multi-year investment supports provinces, territories, and Indigenous communities in wildfire prevention and mitigation. Cost-shared funding agreements require detailed project proposals, budget breakdowns, and compliance with federal procurement and reporting standards.

Indigenous Services Canada Emergency Management FireSmart Program: Ongoing intake until March 31, 2026, or until funds are exhausted. First Nations communities can apply for wildfire risk assessments, crew training, fuel management, and equipment purchases, with proposals reviewed on a rolling basis.

Municipalities that finalize equipment specifications and cost estimates in Q4 2025 can align their applications with these funding windows, ensuring that grant decisions, budget approvals, and procurement schedules are synchronized.

Risks of Waiting Too Late

Project Delays and Missed Readiness Windows

The most immediate risk of delayed planning is missing the 2026 fire season entirely. The Denare Beach fire began on May 6, 2025, and by June 3, more than half the community's structures were lost. Flin Flon evacuated in late May 2025 and remained evacuated for weeks. Equipment that arrives after fire season begins cannot protect communities.

Budget Deferrals and Competing Priorities

Municipal budgets are constrained, and capital projects compete for limited funds. If structure protection proposals are submitted late or lack sufficient detail, finance committees may defer them to the following year, particularly if other infrastructure priorities have better-developed business cases. This deferral can cascade years forward.

Missed Grant Deadlines

Federal and provincial funding programs operate on fixed cycles. Applications submitted after deadlines are typically ineligible, regardless of merit. The FireSmart BC program explicitly states that funding is available "funding permitting" and that applications are processed within the open intake window.

Strategic Recommendations: Q4 2025 to Spring 2026 Blueprint

October 2025: Needs Assessment and Stakeholder Engagement

Key Activities:

Conduct wildfire risk assessments: Review updated provincial fire danger maps, WUI risk classifications, and community wildfire protection plans. Identify priority zones, high-value structures, and critical infrastructure.

Engage operational stakeholders: Convene fire chiefs, emergency management coordinators, public works directors, and finance officers. Define structure protection objectives and operational requirements.

Inventory existing equipment: Catalog current equipment, identify gaps, obsolescence, and maintenance needs.

Research funding opportunities: Review FireSmart, RCF, and provincial/territorial program guidelines. Confirm eligibility, application requirements, and deadlines.

Outputs: Preliminary equipment needs list; stakeholder consensus on priorities; identified funding sources.

November 2025: Specification Development and Supplier Outreach

Key Activities:

Draft technical specifications: Define equipment requirements, referencing industry standards including NFPA, FireSmart Canada guidelines, and provincial operational standards.

Consult equipment suppliers and manufacturers: Request preliminary quotes, lead time estimates, and product availability. Engage vendors through informal Requests for Information to validate specifications and identify potential delivery constraints.

Validate compliance requirements: Confirm that specifications meet provincial trade agreement thresholds, environmental regulations, and safety standards. Engage legal and procurement staff early.

Outputs: Detailed technical specifications; preliminary cost estimates; supplier feedback; compliance checklist.

December 2025: Business Case Development and Budget Finalization

Key Activities:

Develop capital budget submission: Prepare business case for council/finance committee, including rationale (wildfire risk, structure loss data), equipment specifications, cost estimates, funding sources, lifecycle costs, and consequences of not funding.

Align with strategic plans: Link structure protection investments to municipal strategic priorities, FireSmart community designations, emergency management plans, and climate adaptation strategies.

Coordinate with grant applications: Begin drafting FireSmart or RCF program applications if deadlines fall in early 2026.

Internal approvals and contingency planning: Secure endorsements from relevant departments and develop contingency plans if full funding is not approved.

Outputs: Finalized capital budget submission; draft grant applications; management approval.

January–March 2026: Budget Deliberation and Grant Submission

Key Activities:

For Calendar-Year Municipalities:

With budgets approved in late December, begin procurement processes immediately in January. Release RFPs early to maximize lead time for equipment delivery.

For Nova Scotia Municipalities:

Present to council; respond to questions; emphasize urgency based on 2025 fire season impacts.

Submit grant applications with all supporting documentation.

Work through council deliberations and secure budget approval (March/April 2026).

Prepare procurement documents in anticipation of budget approval.

Outputs: Budget approval; grant submissions; procurement documents ready for release.

April–June 2026: Procurement and Contract Award

Key Activities:

Issue RFPs: Post competitive solicitations on required platforms (CanadaBuys, provincial tender sites) immediately after budget approval.

Evaluate bids: Conduct technical and financial evaluations; check references; validate compliance with specifications and trade agreements.

Award contracts: Negotiate final terms; execute contracts; issue purchase orders.

Coordinate delivery and training: Schedule equipment delivery and training sessions for operational staff.

Outputs: Executed contracts; delivery schedules; training plans.

July–December 2026: Delivery, Training, and Readiness

Key Activities:

Receive and inspect equipment: Conduct acceptance testing; verify specifications.

Train operational staff: Provide hands-on training for fire crews.

Update operational plans: Integrate new equipment into community wildfire protection plans and incident response protocols.

Monitor maintenance schedules: Establish preventive maintenance routines.

Outputs: Operational equipment; trained crews; updated plans; readiness for 2027 fire season.

Alberta Structure Protection Program

Alberta's Structure Protection Program provides a provincial model for coordinating municipal and wildfire agency efforts. The program includes pre-positioned sprinkler trailers, trained structure protection specialists, and operational guidelines for deploying equipment in WUI zones. However, provincial resources are finite, and demand during active fire seasons far exceeds supply. Municipalities that invest in their own structure protection capacity can supplement provincial resources.

Conclusion: The Imperative of Q4 Planning

The 2025 wildfire season has made clear that structure protection is a necessity. With 8.78 million hectares burned as of September 16, hundreds of homes destroyed across multiple provinces, and combined insured losses exceeding $1.5 billion from the Jasper, Flin Flon Complex, and Kingston fires alone, Canadian municipalities must invest proactively in structure protection capacity.

October through December 2025 represents the critical window for Canadian procurement officers, fire chiefs, and emergency managers to begin planning for 2026 structure protection procurement. This quarter provides the time needed to conduct risk assessments, engage stakeholders, develop specifications, secure grant funding, and align procurement with budget cycles. Municipalities that act now will position themselves to issue RFPs in early 2026 and award contracts by spring or early summer.

The costs of delay are significant. Compressed procurement timelines increase equipment costs, reduce supplier selection, and risk missing budget windows entirely. Late planning jeopardizes grant funding and leaves communities exposed during the 2026 fire season.

Moving Forward

Review wildfire risk assessments and structure protection needs in consultation with fire services and emergency management.

Initiate stakeholder engagement to build consensus on equipment priorities, operational doctrine, and budget requirements.

Research and align with grant funding programs, including FireSmart BC, RCF, and Indigenous Services Canada programs, to maximize cost-sharing opportunities.

Develop detailed technical specifications and cost estimates in Q4 2025 to support December 2025 or early 2026 budget submissions.

Engage procurement and legal staff early to ensure compliance, competitive processes, and realistic timelines.

Build contingency plans for phased procurement, modular systems, or regional partnerships if full funding is not immediately available.

The 2026 wildfire season will not wait for late-starting procurement processes. Communities that begin planning now—before budget season—will be ready.

For technical guidance on structure protection equipment, consult resources from FireSmart Canada, provincial wildfire agencies (NRCan Canadian Wildland Fire Information System, BC Wildfire Service, Alberta Wildfire, Saskatchewan Public Safety Agency), and industry partners. For procurement support, engage municipal procurement networks, provincial associations (Union of BC Municipalities, Alberta Municipalities, Federation of Canadian Municipalities), and emergency management coordinators.

The time to plan for 2026 structure protection is October 2025. Start now.